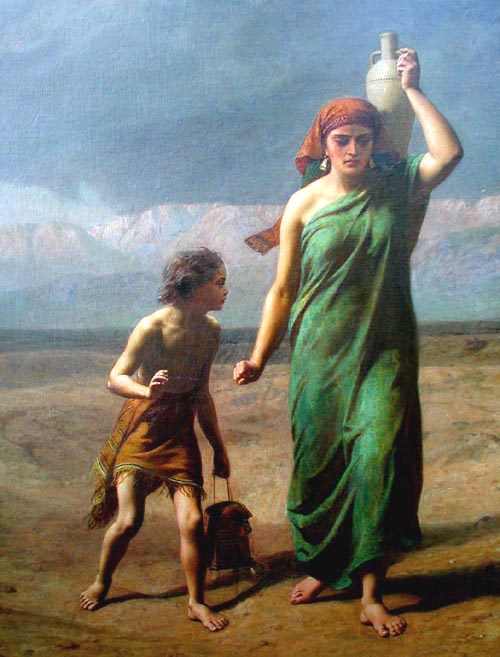

Hagar and Ishmael attributed to Frederick Goodall

This image is courtesy of Clayton and Lesley Sanders. When the painting was found, it was rolled up and in very poor condition. Upon examination and research, it appears that it has been cut down from its original size and therefore leaves out some detail which is believed to be among other things, numerous skeletons and a vulture overhead. The most unfortunate thing is that the signature of the artist was lost. It is almost certain that it is the highly acclaimed painting done by Frederick Goodall that was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1866.

It should be noted that Frederick Goodall did another painting of this subject in 1879 which also appeared in the Royal Academy.

In Frederick Goodall's autobiography he mentions this painting and some of the interesting details surrounding it.

"It will be remembered that when painting in Egypt, an Arab girl crawled over the flat roofs of some houses to get the bribe of half a Napoleon which I had offered if she would sit three times. The difficulty was not to get Arabs to sit once, but to get them to sit more than once. That is the reason I proposed a strong inducement to tempt her to sit three times. I was horrified at the treatment which she received at the hands of her brutal brother, but she would sit and I was very glad I had made three studies of her head, for she was perfect to Hagar."

He also mentions the boy who was used for Ishmael. There was a man in London by the name of John Tropp who had a boy that sat for Frederick.

"This John Tropp was often in prison for begging in the streets. But he did not mind going to prison so much as the punishment of going without his opium. He always kept a supply under his finger nails in case he were locked up for a fortnight. He had a boy who also sat, or rather stood, to me for Ishmael."

The following is taken from the London Art Journal of June 1, 1866, page 178:

"Mr. Frederick Goodall, R.A., has, in his poetic and deeply impressive picture, maintained the position which the works of recent years have won. To fill a wide canvas with two figures, the presence whereof shall be felt in the surrounding solitude, is, indeed, no easy task. Less thought is often involved in crowded compositions, where any defect in the component parts may find compensation in the aggregate. But where figures are few they must be faultless. The subject chosen by Mr. Goodall is perhaps as grand as any which Scripture history suggests. Sarah said unto Abraham "Cast out this bond woman and her son." and she departed and wandered in the wilderness of Beersheba. Here then, in the desert country which extends on the eastern side of the Red Sea, are Hagar and her son Ishmael, just as Abraham sent them away. They cannot long have entered on this waste and wide wilderness, for the water borne in the in the bottle on the shoulder is not yet spent, and the kindled wrath of the woman has not cooled. There is, indeed, nobility and assurance in Hagar's aspect, for she knows that God will make of her son a great nation. Yet the picture tells us, by unmistakable signs, that she is to be an outcast and a wanderer. She seems however, to threaten just as much as she suffers. Her spirit is proud and not easily quelled. All this, too, the picture proclaims. Sympathy, indeed, we believe, has generally been enlisted on the poor outcast's side. The Art-qualities of the work may be thus analyzed: solitude and solemnity in the desert scene, extent in the sweep of horizon, deep shade in the lowering sky, dark response in the purple shadow thrown across the plain. A vulture hovers in the sky, scenting blood; the earth is strewn with skeletons. The only forms of life that walk the earth are the outcast and her son. The figure of Hagar is enhanced to the uttermost, both by nobility of form and deep lustre of colour. Her robe is of blue, passing into emerald; the head dress has the force and brilliancy of the complementary colour, orange. Hagar, we are told, was an Egyptian; a sphinx-like type of face, massive, finely formed, and firmly modeled, pronounces the head in strength. Finally, specially worthy of note is the power maintained in quietism. The effect has been kept down; we feel there is a reserve of force."

Back to Frederick Goodall images. Home